Hungry

If you would like to support my writing, the best way to do that is by signing up as a paid subscriber to this Substack. It’s £3.50 per month, for three exclusive posts a month. This price is very little on an individual basis but adds up to be a substantial relief for my finances and enables me to finish some large projects I’ve got on the go. Thank you in advance.

4 May 1981. In a small, airless room, a family huddles around a bed in a prison hospital. A shrunken figure lies there, tucked under drab woollen blankets. It is a young man, but one almost unrecognisable from the image of him that will circulate globally in the weeks and years to come. Now, his emaciated face is surrounded by unkempt hair. His eyelids are swollen black and closed — he slipped into a coma yesterday — but when open, they are horribly wide and protruding amidst skeletal features, even though he lost the ability to see anything from them about a week prior.

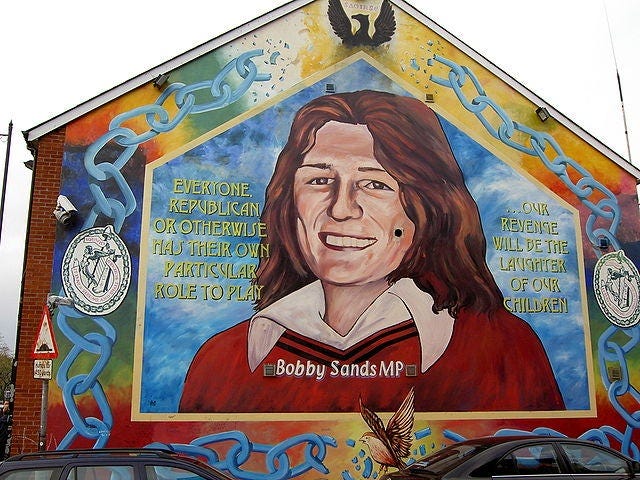

But the way the public will remember Bobby Sands is frozen at around 19 years-old, clean shaven and handsome, with a wide, dimpled smile. The photograph that immortalises him was taken inside the same prison complex he is now dying in. Sands is only 27, but he has spent the majority of his adult life in detention.

When Sands’ body finally gives out, at nearly twenty past one on 5 May 1981, he has been on hunger strike for 66 days. His name passes instantly into legend. He’s the leader of, and first participant to die in the current staggered protest — which follows a previous 1980 hunger strike — and has recently been elected MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone, a turn-up that sets Sinn Féin, the IRA’s political wing, on a course to winning mainstream power.

Of course, Sands has no inkling of the legacy he leaves. Nor do the nine other hunger strikers who follow him into death over the following months, until the strike is ended on 3 October 1981. Francis Hughes, Raymond McCreesh, Patsy O’Hara, Joe McDonnell, Kieran Doherty, Kevin Lynch, Martin Huston, Thomas McElwee and Michael Devine die without ever seeing their thirtieth birthdays or knowing if their protest is successful — whether they have won their comrades the concessions they seek from the British state, chiefly for those detained for fighting in the war ravaging Ireland to be recognised as political prisoners.

The wider impact is more seismic than any of them probably could have dreamed. Then again, those who take a cause to such an end tend to be big dreamers. The ten men become martyrs, Sands canonised most of all. And though their central demand — of having Special Category Status restored — isn’t met, over the next two years, all their other stipulations related to life in prison are. More significantly, they have boosted the nationalist cause beyond belief. Mythology takes root.

Right now, a hunger strike is underway in England that is drawing comparisons to the Irish IRA and INLA activists of 1981. The participants — initially eight, down to three — have been held in UK prisons for over year without trial, well beyond the legal custody limit of six months. They’ve been told they will likely face two years in jail before they get their day in court. They are detained on suspicion of a variety of alleged offences, stemming from two direct action operations in 2024 and 2025, the first at a research hub belonging to Israel’s largest defence contractor — Elbit Systems —, the second at the RAF’s Brize Norton base, the largest in the UK. Palestine Action, now proscribed as a terrorist group, claimed credit for both endeavours, which are estimated to have caused a few million pounds worth of damage.